The Walk, 1992 by Susan Buttenwieser

It isn’t a good week for this. That’s Mike’s first thought when he arrives at work on Monday morning and the receptionist announces that the head of Human Resources wants to see him. A different week, maybe he could have coped with it. But not this one.

“Donny’s looking for you,” she says with a slight smirk. A hint of pleasure.

“Good morning to you too. Do I have any messages?” Mike asks. “And when you get a chance, could you move that meeting with the Sumner Street contractors to Wednesday, instead of tomorrow?”

The receptionist looks at him like he didn’t understand what she just said. “You have to go to Donny’s office,” she repeats the information, slower this time. “Like right away. Don’t even bother with anything else, go straight there. That’s what Donny said I was supposed to tell you.”

“Well, well. Aren’t you doing a good job of it then?”

It’s out of Mike’s mouth before he can do anything about it. He always stressed good manners with his kids when they were little. Please and thank you and all that. People’s feelings are important, he must have said fifty thousand times. Yet he has to admit that it’s somehow satisfying to see that his rudeness has not gone unnoticed, and the receptionist looks startled for a brief moment before turning her attention back to the switchboard.

Mike hesitates, wondering if there’s time to grab a coffee first, but decides against it. When he gets to Donny’s office, the door is closed. Mike does a few neck rolls before knocking and going inside.

Donny’s face crumples up like he might be sick to his stomach when he sees that it’s Mike, right there in front of him.

If only it wasn’t this week.

For one thing, there’s the lump Mike’s wife found. Cath had already been through one mastectomy, chemo and radiation. As they waited in the doctor’s office on Friday, Cath wept quietly while Mike held her hand and tried to maintain his composure.

Then over the weekend they’d gotten a phone call in the middle of the night from this tweaked out girl babbling incoherently about their niece, Marnie. They hadn’t seen Marnie in months, not since Thanksgiving when she’d shown up with this skinny, pale guy who kept nodding off during appetizers in the living room and again when they settled in for the meal. Marnie’s grandmother, who raised her, died several years ago and the loss had taken a toll on her. She dropped out of high school and Mike and Cath never really knew where she was anymore. Marnie hardly said a word during dinner, just shoveled in the turkey like she hadn’t eaten in a long time, and they left before the pumpkin pie was served. Cath later confessed that she’d hidden her purse.

Mike couldn’t understand one word the tweaked out girl was saying. Cath clicked on her lamp when the phone rang by Mike’s side of the bed and he was slowly adjusting to the sudden brightness.

“What in the world is she on about?” He passed the phone to his wife. “Here, you try.”

The heat was turned down and they shivered under the quilt. Mike propped himself up on a pillow and looked at his wife. Her curly hair had just started to grow back, and there was enough to run her hand through a thick wad of wild, disheveled strands. Cath’s eyes were puffy and barely open. She didn’t fully function without caffeine.

“Something about underwater rainbows. That’s all I’m getting.” Cath covered the receiver with her hand. “Honey, slow down,” she said into the phone. “I can hardly hear you. What’s going on with Marnie? Where are you girls anyway?” She squinted with concentration, then sat up straight and reported back to Mike. “Mikey, she’s saying Marnie wasn’t breathing. Oh God. Marnie’s in an ambulance. Oh God, Mikey.”

A February wind pummeled the bedroom windows as Cath somehow managed to get the name of the hospital in Providence where Marnie was being taken and a vague address. Then Cath hurried down to the kitchen to put on coffee and Mike got dressed. He held his wife in the kitchen, nestling his chin in her hair. She handed him a large travel mug filled with coffee, gave him a quick kiss and then he was sitting behind the steering wheel which was so cold, he had to wear gloves just to touch it. He let the engine warm up for a few minutes before barreling along the dark highway, praying his niece would still be alive by the time he reached her. This must have been Marnie’s third or fourth overdose, at least that Mike was aware of. He didn’t know much about heroin or junkies, but he was certain it couldn’t go on like this forever.

That was Saturday night. And now this. This being Donny droning on and on about projections and miscalculations and the dip in the market. Stagnation. Bubbles bursting.

Just between you and me, Donny lowers his voice, the company had been

over-optimistic, made some bad decisions. On top of that, their main competitor is

undercutting them by not working with unions. “We would never do that,” Donny says. “But that kind of integrity comes with a cost.”

And one of those costs, apparently, is Mike. Donny’s the one who suggested Mike think about working here. Took him aside nine years ago while they were on vacation together with their families on the Cape. “I can put in a word for you,” Donny said. “We’re the largest construction company in Boston. It would mean benefits and steady work and being in an office. Not freezing your nuts off in January on some work site. We’re doing really well and for what it’s worth, I’m planning to stay there until I retire.”

They were watching their kids body surfing, the sun dropping down behind them in the water, Cath and Donny’s wife floating on yellow and pink noodles.

Now, Donny sits across from Mike, struggling to make eye contact.

“It’s not about you. It really isn’t,” Donny swallows. Hard. “We can’t justify all the project managers. We just can’t.” It had seemed like a weird move when Donny transferred over to human resources last year, but now it all makes sense.

Stu from security appears, as if on cue. His body fills the entire door frame. “Hey buddy,” he says to Mike. Tries a smile and makes a popping sound with his lips, as if this was just like any other day.

But Mike knows what’s coming, has been watching Stu and Donny doing this since the beginning of the new year. They’ve got it down now, like a dance routine. Walking people to their desks without talking, their faces remaining neutral, expressionless. But right under the surface, if you look closely, there is something more than just relief that it’s not them, something verging towards satisfaction. They move their charges quickly along the hallways made of glass walls built to elicit collaboration. That kind of transparency means everyone can watch, before going back to their own work, pretending to be absorbed in it, even though all they are thinking about is the person being hustled out.

And today that person is Mike. “Come on guys, you don’t need to do this,” he tries. “I can show myself out.”

“Sorry man, it’s nothing personal,” Stu says. “Just proceduraling.”

That’s not even a word, you douche, Mike thinks as they flank him on the way back to his office. The eighth floor has never seemed so vast. How many times has he gone from his desk to HR for some forms and back in less than a minute? But right now, it’s hours from Donny’s office to his, padding along the beige and brown carpeting in their muffled indoor shoes, tracing the path of Mike’s career at this place. The early years at various desks deep inside the warren of cubicles filled with junior staffers. At first, it felt weird not wearing work boots all day long. But several promotions led to an office with an actual door and a window with a view even. On those bitter cold days in particular, Donny had been right. Mike was relieved to be inside and proud at where he had taken himself.

Now he squats down on the floor by his desk. Stu and Donny hover over him to make sure he doesn’t take his Rolodex, files, company paperwork, blue prints, or steal any office supplies. Even the stapler is off limits, Stu explains. Just the personal effects. Mike looks through his desk drawers, shoving the past nine years into one cardboard box. Debris from office parties, joke birthday presents, paraphernalia from conferences and company outings. Shot glasses and a foam finger from the ’86 World Series, various mini state flags he meant to give his kids but forgot, Niagara Falls playing cards, a baseball signed by Carlton Fiske that he won at a company fundraiser for the Jimmy Fund.

When he stands up, it seems possible that his knees could give way. He peels photos from the wall -- his kids’ football games, hockey tournaments, swim meets, Christmases, a Disney vacation with the whole family, all five kids plus him and Cath, beach trips, one with Marnie even during better times. Mike balls up the Scotch tape and throws the sticky wad into the trashcan.

He looks around one last time. At his view of the parking lot, Route 128 behind that, and the reservoir. The small piece of carpet he’s walked across every day, the place where he sat and worked all these years, the walls, the hallway. Then there is more walking.

Past his colleagues, his four-person team, the marketing department, accounting. It feels like the entire division of Northeast Regional Planning is staring at him Even the intern from Northeastern can’t help but sneak a glimpse of Mike being led out.

They pass Sandra who used to want to sleep with Mike. Several years ago, they were seated next to each other at a company dinner, her hand on his thigh the entire evening. Mike went home to Cath though. There were a few other opportunities, a two-day conference in New Hampshire, an overnight team building initiative in Springfield where it almost happened. They never did anything and now she won’t look at him. Not even one last time.

Finally, they are at the front, by the receptionist, where it all began, Mike holding onto his box.

“Think I can take it from here,” he says.

But no, it’s policy. They have to escort him all the way to his car. Stu makes the popping sound again. The receptionist concentrates on the fax machine like she’s pretending not to notice what is happening right in front of her.

Of course, today, Mike parked on the far side of the lot. Blinding sunshine glints off the windshields. There’s only the sound of their footsteps crunching across concrete and the whoosh of cars out on the highway. It is a biting cold morning and Mike regrets not putting on his gloves, his fingers ache as he grips the edges of the cardboard box, cradling his possessions in his arms. Donny walks so close to him that occasionally he brushes against Mike’s right forearm. Stu in his mirrored sunglasses to his left starts whistling as they thread through the rows of cars, backseats smothered in soccer balls, Little League uniforms, Dunkin Donuts Styrofoam cups and Munchkin boxes. Walking past Donny’s Chrysler LeBaron. Stu’s bright yellow Mustang.

It’s when they reach Mike’s Honda Civic that Donny says it. “Hey, no hard feelings, okay man.” He holds out his hand. “We can’t let this get in the way of our friendship. You and Cath…dinner or something. Like really soon, okay?”

Mike considers his options. Spitting into Donny’s outstretched palm. Giving them both the finger and flooring it out of there, his co-workers pressed up against the floor-to-ceiling windows, cheering him on, a possible stirring from Sandra.

Instead, Mike puts down his box and shakes Donny’s hand, before unlocking his car. He sits in the front seat watching Donny and Stu retrace their steps towards the sliding doors. Returning to the safety of their desks and paperwork and phone calls and lunch breaks and end-of-day drinks at Houlihan’s.

The Burlington Mall is only ten minutes away. He could go the cinema there, pay for one movie, then spend the rest of the day sneaking in and out of the other theaters, like his kids always boasted to each other of doing. Buy himself some time while he tries to figure out how to tell Cath.

It’s not just his wife and cancer and his five kids and college tuitions and his troubled niece. There’s Cath’s entire side of the family to think of as well. Her mother in a nursing home. Cath’s siblings, seven of them, plus various husbands and wives. Some of them employed and still married, some not. All those nieces and nephews, a few with children of their own. And everyone’s problems. Affairs, separations, divorces, custody battles, bankruptcy, damaged cars and homes, bar fights, illnesses, juvie. All that endless need.

Everyone’s first call is always Mike. Mikey boy, Cath’s brothers say when there’s been a car accident or an arrest or someone drank too much, making an effort to sound upbeat on the phone. Try your Uncle Mike, Cath’s sisters snap at their kids. Because I’ve had it up to here with your bullcrap.

He puts the key in the ignition, reverses out of the parking space and crosses the outer edge of the lot, takes a right on Juniper that leads him to the on-ramp. In minutes, he has folded in with the rapid current of cars on Route 128. Mike, clean-shaven and in a suit at 9:53 on a Monday morning, with nowhere in particular to go.

© Susan Buttenwieser, 2018

Susan Buttenwieser's fiction has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize and appeared in Epiphany, The Cossack Review, Atticus Review and other publications. She contributes news articles to Women's Media Center and creative nonfiction to Brain, Child and Mamalode, and received several fiction fellowships from the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. She also teaches creative writing in New York City public schools in high poverty neighborhoods, and with incarcerated women and older adults.

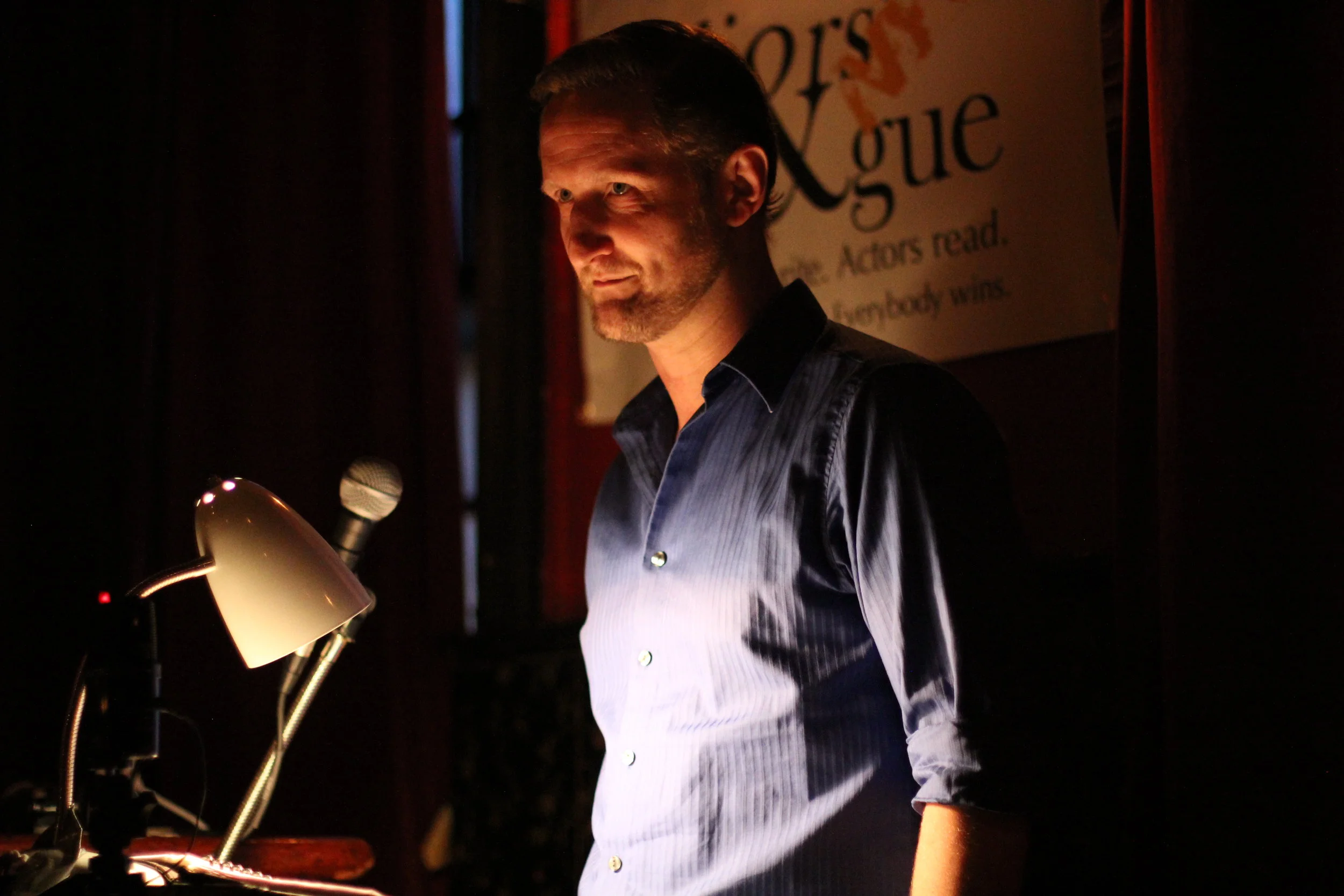

The Walk, 1992 was read by Rudi Utter on 6th June 2018 for Questions & Answers