Old Time Pieces

by Mark Sadler

Thomas William James harboured pretensions of godhood. His intent was on dragging the remainder of humanity into a future of his own design, offering nary a backward, sympathetic glance to anyone who failed to keep pace. I would hazard a guess that very few people who locked antlers with him came out on top.

It was a trio of Scotsmen; myself, Bill Ellis and David Browman, who sounded-out his Achilles heel and brought the titan crashing down to earth. To Thomas's credit he never failed to take us seriously. He told me once how, as a young man, he defied the wishes of his politically-influential father, and departed Chicago to fight in Vietnam. He learned there to never underestimate the ability of those with scarce means to snatch a victory in the face of overwhelming odds.

Yet he overlooked the history of Dalbrae which is strewn with invasions and sieges. Resistance is written into our DNA in illuminated Latin script. Our near ancestors, some still living, might say that what we experienced at the hands of Thomas and his army of lawyers pales next to what was endured during the war, when German U-boats patrolled our island's waters. Even further back, the time-worn ghosts of our forefathers would likely grumble that all of that was nothing when compared with the Viking incursions.

The raiding parties arrive and leave with the tide. Still our little town of Granrathy clings to the western shore, behind the weedy rubble of its coastal defences, the North Sea pawing strips of mortar from the cross section of our cracked slipway. A double row of austere stone houses, some bearing a coat of whitewash, line-up like castaways on a stony beach awaiting rescue. Inland, there is nothing more than a handful of isolated smallholdings. A solitary paved road, known as the Bonecarr, leads to the Daernkirk, the island church that loses itself in the hill mist. The last building alongside the road, before it begins its ascent, is traditionally home to the town stone mason. In the yard there is always a pile of fist-size rocks. On those occasions when we assemble to bury one of our own, we stop there and take one of these stones in hand, to carry with us to the cemetery and build the cairn over the filled-in grave.

In 1901, a different kind of stone streaked across the heavens, sprinkling ballast across the roof slates in the town. It impacted high on the Bonecarr then hobbled downhill, rolling to a halt in the mason yard where it was found the following morning: An opaque white crystal, like a boulder of ice, its surface-sheen swimming with iridescence. At night it glowed. The mason then was Stanley Moy. He broke it up and added it to his pile of rocks. For a while it was customary to insert one of the glowing stones into the heart of a new cairn, so that it lit up from the inside. People called them elf forts. At night their collective radiance was visible in town, and off the coast, as a faint disturbance in the air.

A century passed, then a geologist named David Browman visited the mason yard and took a sliver of the pale stone, that he spied buried in the dirt, for analysis. A fortnight later myself and Bill Ellis, who is our current stone mason, got on the boat to Airkirk, on the mainland. We met David in a public house by the harbour, called The Finny.

“It's mature quartz,” he said, pushing a flimsy plastic folder across the table, through a puddle of spilled beer. I flicked through the short report that was filled with baffling equations and colour-printed spectrometer readings.

“In layman's terms?”

“It's a variant of quartz that formed very early in the history of our universe. It has some unique properties.”

“That would be the incessant glowing,” chimed Bill.

“Aye, there is that. But put an electric current through it and you can generate needlepoint pulses so precise that you can measure timings down to billionths of a second.”

Bill took the report from me and began to leaf through without reading.

“So, all I need to do is get some of this quartz put inside a watch and I'll never be late for anything again,” he mused. “It sounds like my idea of hell.”

“What you have sitting out in the open is an extremely rare commodity, many times more valuable than gold,” warned David. “I can think of any number of people and organisations who would like to lay their hands on it. So, you might want to do something about that.”

Bill and I drank up. David was only halfway down his glass. As we got up to leave, Bill laid a hand on his shoulder.

“It would save us some trouble if you could keep all this under wraps.”

“It's gone through the lab now so it won't be up to me. I'll do my best to keep the location confidential.”

~

That was how Granrathy came to be on the radar of Thomas James. A man like that has ways of finding out about things that he can turn to his advantage. Alan Wyville, who was town alderman, mentioned to myself and John Rumsey, that an American businessman, a billionaire, had been in contact:

“He wants to purchase the glowing stones in the cemetery. In return he is willing to invest in developing Dalbrae's infrastructure.

“I'll add it to the agenda for Sunday's meeting.” sighed John.

~

There is a fifteen minute film of Thomas James, walking briskly across Chicago, with an interviewer and a cameraman in tow. He crosses busy streets without changing his pace and without the approaching cars slowing down. It is as if he is perfectly in tune with the universe. Sometimes his hangers-on get left behind and have to race to catch up. The spectacle is strangely hypnotic and it gave me my first inkling that there might be trouble looming on the horizon.

The town meeting was a tumultuous affair. The cemetery was the final item on the agenda but people kept bringing it up ahead of schedule. Alan had to shout to keep order. Ursula Moss struggled out of her chair, walked right down to the front and addressed him directly:

“You will not lay a finger on my family's grave.”

The proposal was laid out. The quartz would be removed respectfully and the money raised reinvested in the island.

“Before we take a vote, Mr James has kindly joined us tonight,” announced Alan. “I would like to give him the opportunity to address the floor. Thomas, if you would come up.”

Thomas James had quietly entered the hall after the meeting began. He advanced along the central aisle on a current of murmured disapproval; a man with the face and bearing of a general, dressed in a long, black woollen coat. A frizz of ginger hair covered his bald scalp, as if it was re-growing. He had a direct way of speaking, of framing his opinions as objective truths:

“Some of you may know that one of my companies manufactures luxury watches and chronometers. The mineral in your cemetery will allow me to produce high-quality, pinpoint-accurate timepieces. I am prepared to offer you a share in the profits and a pledge to develop your community's roads and telecommunications.”

Somebody at the back of the room shouted: “Why don't you go into space and find your own meteorite?”

“Well that's something we are working on doing.”

“Don't trouble yourself to come back!”

The room churned with dissent. The vote was overwhelmingly against selling. Thomas retreated to the Gowfeddy Guest House for the night. He departed the following morning by private launch. As the boat was leaving the harbour, one of the fisher lads hurled a rock that had been painted white into the engine wash.

I think Thomas took note of that. It gave him an indication that there was anger in the community; that he could turn it inward and pit us against one another. As Andy Rankins observed: “With people like Mr James, the game only ends when they win.”

I believe Thomas was an honourable man, despite the manner in which he attempted to strangle us into submission. He stayed inside the law. He knew how to identify and exploit weak spots and he was unpredictable in his choice of targets:

Dalbrae's fishing grounds are located around a headland called the Spornie that deflects the wind from our calmer harbours. It was this wind that carried our boats back home. No need to run the engine and waste money on fuel.

There had been talk of a wind-farm on Begfinn Island, with the usual concerns raised regarding the impact on the environment. Into this debate stepped Thomas James with his unobtrusive air-harvesting technology. He had it up and running on Begfinn within nine months. We were the first to notice the change. The wind that chased around the Spornie was suddenly gone, ensnared within Thomas's giant net. The labouring engines of our fishing boats fought the tide all the way home. The cost of running the fleet rose significantly.

October, 2005: A conference call. Seven of us gathered in the freezing church hall around a four-way telephone speaker, set-up on a fold-away table. Derek Fiddes, who was in a jovial mood despite our circumstances, led the charge:

“Well, Mr James, it seems that you have taken some of the wind out of our sails.”

A familiar voice, carried all the way across the Atlantic:

“You have no idea how easy it would be to fix that.”

“You would want something in exchange, of course.”

“Anything I accepted as recompense would be removed respectfully.”

“I take it that, if we forgo your offer, the thumbscrews will be tightened,” said John Rumsey.

John was right. Thomas's next target was a proposed marine research facility to be built on the isolated east coast of Dalbrae. With it came the promise of two new roads that would open up the interior, better internet connection, an emergency medical centre and a helipad.

We got word in July that the funding had fallen through. A few days after, Thomas James stepped-in to save the project, which was to be re-sited on Helmsnet Island.

There was another town meeting. This time around the radiators in the hall were blazing. It was uncomfortably hot. A divide was forming within our community:

“For the love of god just sell to him and be done,” raged Mary Leckenby, her face twisted with impotent anger.

Enough of us dug in our heels to keep Thomas at bay, though afterwards the mood was downbeat. Alan looked rattled:

“If we carry on like this I wouldn't put it past him to buy the land out from under us.”

“Oh come on, let's keep things in proportion,” chided Bill.

Another twelve months slipped past. During that time there were two further public votes. Both times, the margin was diminished. Thomas had taken-over the ferry to the islands. He subtly altered the timetable, scaling-down the Dalbrae service.

We began noticing strangers loitering in the vicinity of the graveyard. They were probably day tourists, but by that time our paranoia was beginning to run rampant. We drew up a rota of volunteers to stand watch.

I was on sentry duty one evening in November, when I saw a familiar black Mercedes advance through the dusk along the Bonecarr. It drew to a halt halfway up. A figure got out from the back and began to walk uphill along the middle of the road. I knew it was Thomas James by the gait. At the entrance to the cemetery he removed his hands from his long black coat and held them just above his head with his elbows bent.

“I come in peace.”

He sat down next to me, gazing out over the town, as the outlines of the buildings faded into black and were replaced by golden pinpricks of light.

“I knew when I first saw this place, I was going to buy into it,” he said.

“Are you here to tempt me with all the rich of the world, Mr James?”

“I'm giving you a dose of reality. Let me tell you something: On the mainland my wind-farm provides free energy to schools and hospitals. I've created jobs in developing industries. Jobs that will still be here in twenty years. I've built new roads. My ferries have strengthened the ties between the islands. On Dalbrae you might think of me as the devil. Outside of this community I'm the closest thing there is to Santa Claus.”

“And we would share in your bounty if we only made one small concession?”

“Something like that.”

“There is a feeling that if we let a man like yourself take whatever he wants from us, he will never stop.”

“I'm not going to take your stones, Alexander. I'm the guy who's been preventing other parties from stealing them out from under you. You are going to give them to me. You won't want to, but you will because the benefits will be too great to ignore and the costs will be too heavy to bear.”

“You might be surprised.”

“I doubt it. Look, I respect your moxie but this fight is over and you lost... You know, when I was a kid I taught myself how to judge the speed of cars, how long it took doors to swing closed, that kind of thing. I taught myself to move effortlessly through the world at my own pace. I was always in the right place at the right time. To an observer it looked like the universe was working with me. Most people don't see beneath the surface. They look for the guy who seems like he's most in charge and they follow him.”

He glanced around the cemetery.

“You really have people guarding this place 24/7?”

“Pretty much.”

“On Christmas day?”

“I've got the midday to 8pm shift.”

“I'm spending Christmas with my family. You should too.”

He got to his feet and walked away. At the lychgate he called out:

“Nobody is going to steal your stones, I promise.”

I watched him move downhill, towards a pair of headlamps waiting for him in the darkness.

~

“We've got to come off the defensive.”

I was surprised by the conviction in my voice.

“This is your idea?” inquired Bill.

“The counter attack is my idea. David came up with the plan. Another thing: Alan can't know.”

That night, we removed the glowing rock from the cairn of my great grandparents. We replaced the loose stones with as much care as we could, but to my eyes it has never looked right again. The outline has changed and, of course, it no longer shines at night.

David brushed the lump of quartz with his chemical solution.

“The mineral structure will begin to break down, but not for a few months.”

It was David who handed the adulterated stone over to Thomas in person. A week later Thomas held an auction Chicago: The quality timepiece of your choice, regulated to pinpoint accuracy by mature quartz. The bidding went through the roof.

The first Alan knew about it was when the payment appeared in the town bank account. Naturally he was furious. That was nothing compared to his mood when Thomas James's mature quartz watches and chronometers began to lose time as the mineral started to deteriorate. The stock in TJ Holdings plummeted and its founder's position leading the company was called into question.

“He's threatening to sue us.”

“Oh, for what?” quarrelled Bill. “The only lesson to be learned here is buyer beware.”

“He doesn't need to win. All he needs to do is tie us up in the courts for years and he'll bleed this whole community dry.”

“Bill, show Alan the news footage,” I said.

We cued-up the film on the rumbling old office computer: Thomas James stammering his way through a press conference. He departed the podium in the wrong direction and had to be led back across the room.

“He's off-kilter. We've broken him,” I said.

“At the very least we've bloodied his nose,” added Bill.

~

The next day Thomas James was killed crossing the street outside his office building. He misjudged the speed of the traffic and was knocked down by a taxi.

The threat of legal action still lingered, though even Alan had to admit that the impetus appeared to have stalled. Finally we received a letter from Thomas's daughter and sole heir, Olivia James. In it she assured us that no further action was to be taken against Granrathy. She no had designs on our island's resources, but she would honour her father's commitment to protect these resources from others. She would restore the ferry service to its original schedule.

She closed her letter with the line:

“You have made your point.”

Did we go too far, I wonder? We did not wish harm to come to Thomas James. We merely wished him to leave us in peace. Granrathy endures until the next siege. We are mostly all still here and will remain so, until it is our turn to be carried up the Bonecarr.

On the summit of the hill above the town, our dead mark their time on this earth with soft light, but they do not keep time for the living.

© Mark Sadler, 2019

Mark Sadler lives in the English town of Southend-on-Sea, with a chameleon named Frederic. His short stories have recently appeared in The Ghastling and in Litbreak Magazine. He is writing a rather long novel that explores the conflicts arising between old-world paganism and contemporary civil engineering.

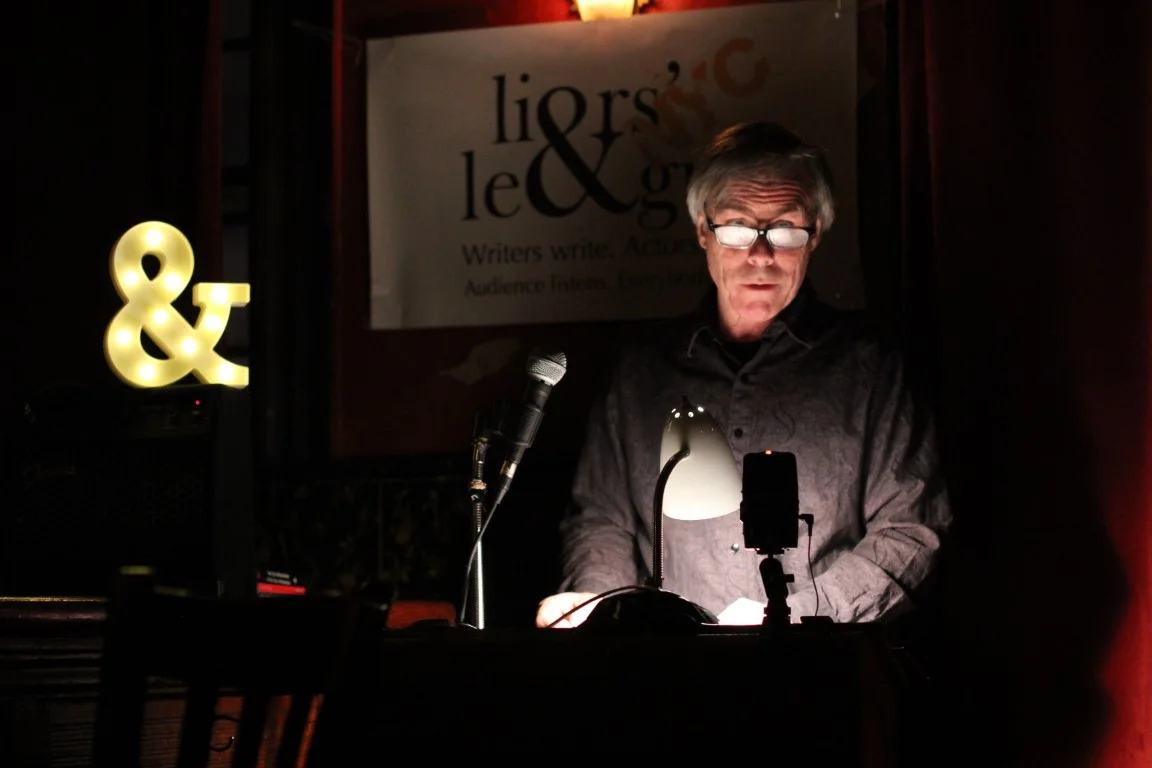

Old Time Pieces was read by Mark Woollett on 6th February 2019 as part of the Plots & Schemes edition.