The Doctor Of Ethology Presents His Findings

by Richard Smyth

The doctor of ethology fanned his notes on the lectern.

‘Thank you all for coming,’ he said, or something like it.

The professors nodded, so as to say: proceed.

‘I will first deliver my key findings,’ he said.

‘Do,’ encouraged the professors.

‘They attach great worth,’ he said, ‘to conditions of dissociation and delusion.’

The fourth professor from the left raised his eyebrows.

‘Delusion?’

‘And dissociation,’ the doctor of ethology confirmed.

‘I find your terminology somewhat imprecise.’

The doctor of ethology fingered his collar.

‘In my paper I adopt the terms they themselves give to these conditions,’ he said. ‘“Wishing”,’ he said, ‘and “hoping”.’

It should be explained that the doctor of ethology was not in fact a doctor of ethology, as he did not have a word for ‘doctor’, nor a word for ‘ethology’. It should be noted, furthermore, that the lectern on which he fanned his notes was not a ‘lectern’ as we would understand the term. Nor, for that matter, were his ‘notes’ ‘notes’ or his ‘collar’ a ‘collar’. He addressed the professors not in English but in a numeric language with a place-value derived from the reciprocals of twin primes. The professors in fact had no eyebrows. The doctor of ethology had no word for ‘hoping’.

‘The inclination to prefer that-which-is-not to that-which-is,’ he said, ‘is a category of dissociation highly prized among their kind.’

The second professor from the right removed his spectacles and blinked.

‘Concepts of that-which-is-not? In a meat-based species?’

The doctor of ethology gravely inclined his head.

‘The first time, we believe, that this behaviour has been observed within a meat-based phylum,’ he said. ‘Previous investigators, such as –’ and here he pronounced the name of a rival doctor of ethology, which consists of digits numbering 2 times 10 to the 566th power, and has no near equivalent in English – ‘erroneously presumed that the high regard in which their experimental subjects held such dissociative states were aberrations – instances of severe personality disorder, perhaps – and that the type specimen of the species would be found to display no such inclination toward that-which-is-not.’

‘And how many subjects were thus dismissed?’

‘A little over seven billion.’

‘And yet you – ’

‘Yes. Having surveyed the literature and conducted our own extensive research, we have concluded that these subjects were not, in fact, aberrant specimens. They were, in fact, the only specimens. “Wishing”, we concluded, is not a disorder – for them.’

The oldest professor chuckled and buffed his spectacles on his cuff.

‘This is surely nonsense,’ he said.

‘And yet it is that-which-is,’ the doctor of ethology said.

It should be explained that the doctor of ethology did not use the word ‘nonsense’. Neither the professors nor the doctor were aware of any concept equivalent to that of nonsense. In extremis, the doctor of ethology coined a new word, utilising a variation on the new sub-language derived from prime k-tuplets that he had had to invent a few sentences earlier in order to express the concept of a ‘personality’.

The youngest professor hunkered forward in his seat.

‘Tell me,’ he said, ‘about the “hoping”.’

The doctor of ethology drew a paper tissue from his breast pocket and dabbed at his brow.

‘Very well,’ he said. He drew from his folder a new and thicker sheaf of notes.

‘Your findings were extensive?’ said the third professor from the left.

‘The field of human hope,’ the doctor of ethology said, ‘is to all intents and purposes an inexhaustible resource for the ethological researcher.’

‘Then proceed,’ said the second professor from the right.

‘I shall,’ the doctor of ethology said. He set himself at the lectern. ‘Around half of the human life-span is spent in hoping.’

The oldest professor interrupted with a raised forefinger.

‘Only half? An aberration, after all, then. A characteristic of the undeveloped type.’

‘No.’ The doctor of ethology blinked defiantly. ‘Half, as I said, is spent in hoping. As a general rule, this is the first half. The remainder is spent in wishing – specifically, a sub-category of wishing that they call “regret”. May I proceed?’

The professor, chastened, gestured in the affirmative.

‘Well, then. Half of their lives they spend in hoping. I have drawn up a list of what I term “hope categories”.’ He plucked a page from the sheaf. ‘With your permission?’

‘Indeed,’ the oldest professor nodded.

It should be explained that the doctor of ethology was now addressing the professors in a multi-dimensional numeric language derived from the complex conjugates representing the concepts of ‘personality’, ‘wishing’, and ‘hoping’. What we would characterise as ‘sentences’ now took the doctor of ethology fourteen million years to deliver.

The doctor of ethology did not in fact have either a breast pocket or a brow. The oldest professor did not in fact have a forefinger.

‘We can say,’ the doctor of ethology said, leaning on the lectern, ‘that hoping, while not evidently a dissociative state, consists in a degree of delusion as regards that-which-will-be, and is predicated upon a preference, apparently inherent in the species, for that-which-will-probably-not-be. Examples include lasting physical firmity, monetary surplus, uncompromised emotional intimacies, uncompromised genital intimacies, and the prolongation of intellectual function consequent to total brain-death.’

‘You need not talk down to us, doctor,’ smiled the second professor from the left. ‘Impress us, please, with your command of their vernacular.’

‘Very well.’ The doctor of ethology cracked his knuckles. ‘To put it as they would put it, “Health”, “Wealth”, “Love”, “Sex” and “Heaven”.’

There was a brief ripple of appreciative applause.

‘And there are many more,’ the doctor pressed on, warming to his theme. ‘The mechanism of “Hoping” can be applied to almost any field of human endeavour. To list a representative sample: baseball, badminton, marriage, the crossing of a thoroughfare, birdwatching, war, bowel evacuation, job, football, bomb disposal, spelunking, meteorological conditions, a public demonstration of basic probability mathematics termed ‘lottery’, and water polo. There are others, but these examples should suffice.’

The second professor from the left asked: ‘What is “job”?’

The third professor from the right asked: ‘What is “war”?’

The oldest professor asked: ‘What is “water polo”?’

The youngest professor asked: ‘Can you tell us again about “love”?’

The doctor of ethology sighed again.

‘When I publish my findings,’ he said, wearily, ‘I shall be sure to include a glossary of these technical terms. In the meantime, perhaps I could finish my presentation?’

The professors, murmuring, assented.

‘The probabilities prevalent in instances of “Hoping”,’ the doctor proceeded, ‘are, as has been established, widely variant but consistent in expressing a preference for that-which-probably-will-not-be. Indeed, our paper demonstrates that where probability approaches 1, hoping approaches 0. The life of each human culminates in the subject being demonstrably – if I may be forgiven a further technical term – “dead”. And yet the proportion of hope expended on “death” is negligible. And we are left with a question: why do humans not hope for things that are certain to happen?’

‘Why do humans hope at all?’ put in the oldest professor.

‘It is what humans do.’

‘Hoping for that-which-probably-will-not-be is as absurd as’ – he framed the word uncertainly ‘wishing for that-which-is-not.’

‘We must not presume to impose our own values on other life-forms, however primitive,’ the doctor of ethology said with a hint of asperity. ‘To conclude. It may be that humans embrace the dissociation of wishing and the delusion of hoping because – inasmuch as a human has a capacity for choice – they choose to. More probably, they do so without knowing that they do so.’

‘Then why would they have given names to these things?’ challenged the third professor from the right.

‘For a negligible fraction of a human life, the human may be aware of “wishing” or “hoping”. For the remainder, the human is not aware. But it is nevertheless what the human is doing.’ The doctor of ethology closed his folder of notes. ‘There is much further study to be done,’ he said. ‘Good day. Thank-you for your time.’

The professors silently watched him go. One hoped for hope. One wished for sex and war. One wished for spelunking. The youngest professor hoped for love.

It should be explained that the list of human hopes alone had taken the doctor of ethology sixty-eight billion years to express in terms of pi-dimensional imaginary quaternions. The terms that he used for ‘spelunking’, ‘sex’ and ‘bowel evacuation’ could only be distant approximations of what we would understand by these terms. In actual fact, neither the doctor of ethology nor the professors understood the concepts of wishing and hoping. In actual fact they did not wish for anything. In actual fact there was no hope at all.

© Richard Smyth, 2013

Richard Smyth's short fiction has appeared in Litro, The Stinging Fly, Cent, The Fiction Desk and Vintage Script; his first novel, Salt Pie Alley, will be published by Dead Ink in 2014. He's also the author of two non-fiction books, numerous magazine articles, a bunch of crosswords, and many hundred quiz-show questions.

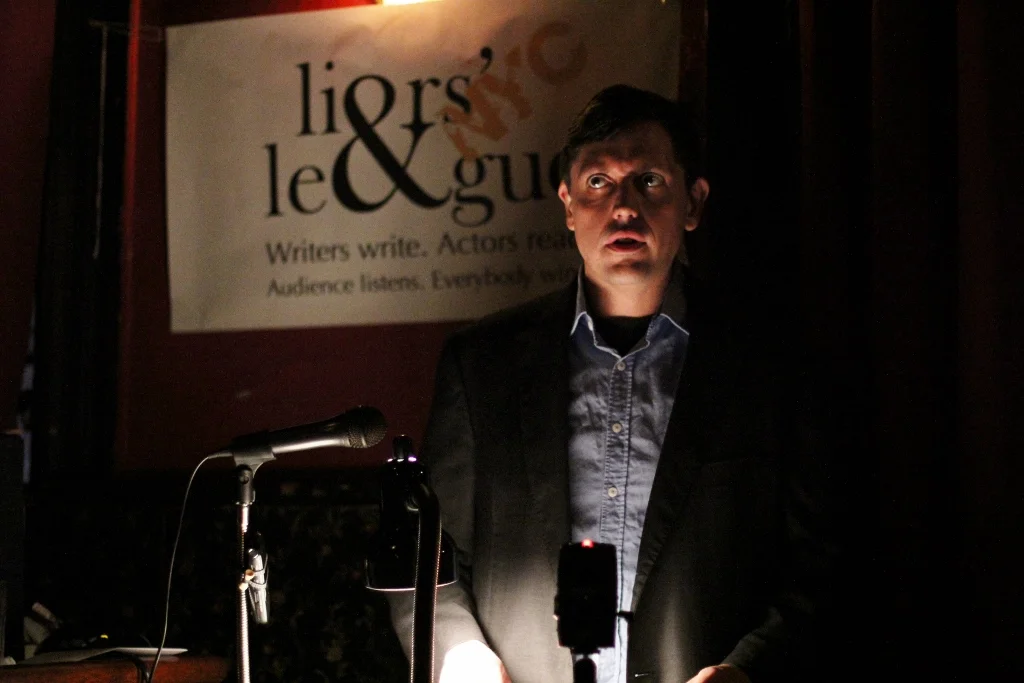

The Doctor Of Ethology Presents His Findings was read by E. James Ford on 4th December 2013